Navigating behavioural biases, market volatility, uncertainty while investing

article • Investment Management

Waterfield Advisors

2024-10-17 | 5 Minuntes

In a lecture given by George Soros at Central European University on October 27, 2009, the renowned hedge fund manager explained the concepts of fallibility and reflexivity. He first introduced these concepts in his book "The Alchemy of Finance" (1987). Soros said, “In the course of my life, I have developed a conceptual framework which has helped me both to make money as a hedge fund manager and to spend money as a policy-oriented philanthropist. But the framework itself is not about money, it is about the relationship between thinking and reality, a subject that has been extensively studied by philosophers from early on.”

While exploring the concepts of fallibility and reflexivity, Soros explains, “I can state the core idea in two relatively simple propositions. One is that in situations that have thinking participants, the participants’ view of the world is always partial and distorted. That is the principle of fallibility. The other is that these distorted views can influence the situation to which they relate because false views lead to inappropriate actions. That is the principle of reflexivity [...] Self-reinforcing but eventually self-defeating boom-bust processes or bubbles are characteristic of financial markets, but they can also be found in other spheres.”

Broadly speaking, Soros brings together philosophy, his life experiences, financial market returns and economic theory. More specifically, he shares the fundamentals of his guiding philosophy– which helped him navigate the 2008 financial crisis – for looking at the future and anticipating crises.

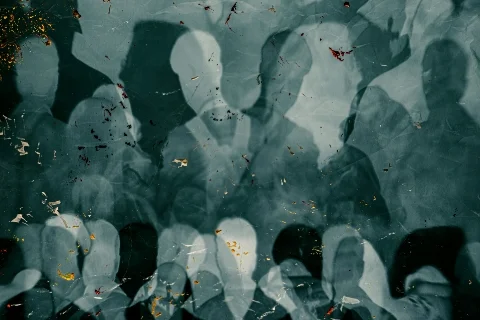

I am reminded of Soros and his guiding philosophy for navigating crises at this juncture, where we all find ourselves amidst a Global Election Supercycle, and when financial markets are experiencing rapid and unpredictable movements, driven by significant political and economic changes, such as India’s election results, the Trump assassination attempt, Joe Biden dropping out of the election race, movement in the Yen, and the recent rally of US Small midcaps vs. the Magnificent 7. With such unpredictabilities at the forefront of everything we do, a question I ask myself often is, ‘Is there a way to forecast market movements?’

The answer to this admittedly age-old question is, I realise, simple and obvious, and yet one that is difficult to digest. The short answer is: We cannot forecast market movements because they are unknown unknowns. A longer answer is: Financial markets are influenced by a vast number of interdependent variables and it is tough to isolate the effect of any single variable. The complexity of financial markets, coupled with behavioural factors and external shocks, means that predictions of market movements are inherently uncertain and intrinsically unpredictable, making such events unknown unknowns.

Still, it is important to try and understand how we can best navigate and prepare for uncertain events, even if we don’t know what those uncertainties may look like. Here, two approaches are key to planning for uncertainties: The qualitative approach and the quantitative approach. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches are indispensable for planning and managing financial market uncertainties. While qualitative methods provide deep insights into investor behaviour, sentiment, and potential risks, quantitative methods offer precise measurements, statistical validation, and predictive capabilities.

Planning and Managing Uncertain Events

Quantitative Approach:

During volatile times, the return of capital is more important than the return on capital. Keeping a margin of safety is crucial, which might mean a higher cash allocation, buying insurance, or hedging against unforeseen events. Avoiding FOMO is imperative, though this is much easier said than done. In any case, an individual’s investment plan should align with their own risk tolerance and circumstances, which can be categorised as conservative, moderate, balanced, or aggressive, with different asset allocation mixes.

Qualitative/Behavioural Approach:

When it comes to the qualitative approach, it is crucial to understand the human biases that can impact one’s decision-making when it comes to investments. These biases can be categorised into:

- Cognitive Errors: Conservatism, confirmation, representativeness, illusion of control, hindsight, anchoring, mental accounting, etc.

- Emotional Biases: Loss aversion, overconfidence, self-control, status quo, endowment, regret aversion, etc.

The cognitive and emotional biases are deeply rooted in human psychology and behaviour, making it difficult to reduce or eliminate them from our decision-making process. Moreover, cognitive biases, such as automatic thinking and reliance on heuristics, often operate unconsciously, which makes it difficult for us to even recognize these biases, let alone be able to control them. Emotional biases, though irrational, have the power to override rational thought processes. Psychological resistance, such as cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias are also at play, further complicating efforts to reduce biases, as people tend to avoid information that conflicts with their existing beliefs.

Trying to reduce or control these biases is akin to timing the market—challenging and often impractical. Similarly, just as it is nearly impossible to perfectly time the entry and exit of stocks, it is almost impossible to accurately time the entry and exit of various asset classes. Therefore, to shield yourself from market volatilities, it is indispensable to build an all-weather portfolio, comprising traditional assets (equities and fixed income), inflation-protecting assets (commodities), and aspirational assets (alternate investments like venture capital, private equity, hedge funds, venture debt, performing credit).

Financial markets go through boom and bust cycles, which are becoming more frequent and volatile. Therefore, flexibility and humility in adapting to new information and facts, echoing John Maynard Keynes sentiment: “When the facts change, I change my mind – what do you do, sir?”

This mindset applies not only to finance but to life as well. Events beyond our control challenge our predictions and behaviours. As humans, we inevitably impose our emotions and biases on our decisions, sometimes at the cost of acknowledging the facts. Embracing the complexity and unpredictability of the world, while staying disciplined and flexible, can help navigate through uncertain times.